I have been working slowly on this “big” measurements post. Don’t run away at the sight of the word “big”! Measurements are really important – without them you are operating open loop. And yet I see so many teams and organizations who either don’t measure, or measure stuff they don’t need, usually at the expense of measuring stuff they do need. I verify Douglas Hubbard’s Measurement Inversion law[i] at nearly every client I visit, and that is really sad. Perhaps this post will help someone, somewhere, improve their measurements and objective feedback discipline. Speaking of which, I would love your feedback on this post – thanks.

Contents

- Three-tier Measurement Loop -this brief framework discussion is necessary to some of the rest of this post’s content

- Simple Steps to Measuring (Closing the Loop!) – I really wanted to start here; too many measurement posts start with theory and are less helpful to those who simply want to measure the right stuff

- Practical Measuring Guidelines – ok, now some guidance, I’ve tried to keep it practical; please pay special attention to GQM and go see the GQM reference if that’s new to you

- Disciplined Agile Delivery’s Principles on Measurement – Scott Ambler has some good advice on measurement and I’ve repeated some of it here for good measure

- A list of potential (mostly control) measures for Agile – Agile leverages control measures a lot, and they can be useful; one of the best sources is Agility Health Radar (for more on AHR see near the bottom of the Guidelines section) but here is my list as well

The Three-tier Measurement Loop

I and some of my colleagues in a former life frequently used a three-tier measurement framework to reason about needed measurements, and I still do so. The loop is straightforward and is a necessary precursor to the discussion that follows:

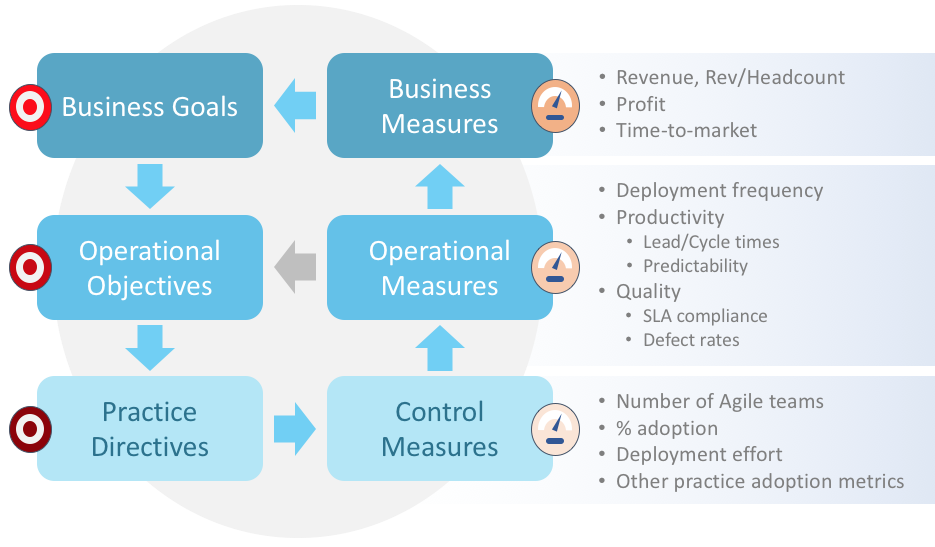

- Business Goals: first, determine/understand your desired business level results, such as revenue, profit, etc.

- Operational Objectives: set operational objectives by reflecting on your situation and your business goals to determine what short term outcomes you wish to achieve. For example, “we want to improve our profit margin so reducing cost would help with that, therefore we want to reduce defects and move them to the left, since that improves our cost profile.” Operational objectives might include quality, predictability, perhaps time-to-market though this is sometimes perceived instead as a business goal, and productivity (though productivity is notoriously difficult to measure without adversely affecting other things like team cohesiveness and capability.)

- Process Directives: if these operational objectives are to be achieved, what process changes should we make to do so? A common answer right now is for shops to decide to take on one or more elements of an Agile process such as Scrum. This is a reasonable process decision.

- Process Control Measures: if we have decided on process directives, how do we know that we are successfully executing in accordance with these decisions? We need measures, and perhaps a dashboard, to tell us these things. If we’ve decided, for example, to “become more Agile over the next N months”, then presumably we’ve defined what that means and we need to know how we’re doing toward that goal. Control measures should be designed to tell us this, and they should be placed on a dashboard where they are easily found so that question can be answered by anyone at any time.

- Operational Outcome Measures: whatever our operational objectives are, we need to measure those outcomes to understand whether we are achieving those objectives, e.g. defects and defect rates for quality.

- Business Result Measures: my guess is your company already has these. If not, then you’re probably pretty small and privately owned; nonetheless, now is a good time to put them in place!

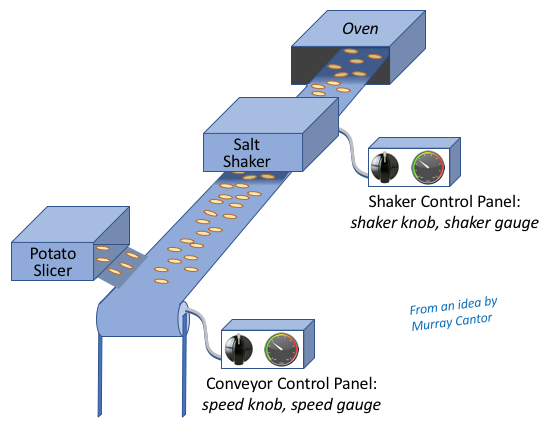

- My mentor Dr. Cantor would speak of the following vignette as a way to motivate this three-tier scheme. Suppose you wish to manufacture tasty potato chips (crisps if you’re from Great Britain). You put together a conveyor that allows the potato slices to go through a salt shaker at some conveyor speed, and then an oven. An important element of selling more chips is flavor, and the salt content of each chip is part of that. You can vary the speed of the conveyor, or vary how much the salt shaker shakes – those are the two things you can do to vary the chip flavor that results from salt content. (There is no flavor knob you can twiddle – clockwise for better flavor! – much as we might wish we had one.)Thus, your desired business result is to sell more chips (revenue). Your operational objective is to get the salt content just right (so that you sell more chips). Your taster might be telling you “um, not quite salty enough”. Therefore, you decide to decrease the conveyor speed a little, and/or increase the shake on the salt shaker. You note the shake frequency gauge and the conveyor speed gauge, and you adjust the two adjustment knobs a little, and note the changes to the two gauges to confirm your actions. In doing this you’re hoping that the taste will improve, but you don’t know. You do know that you’re making things a bit saltier. This first step is feedback from process control measures of shake and speed in light of the process decision regarding them.Now your taster tastes the affected chips. “Tastes better” she says. Now you have an operational outcome measure as feedback to your operational objective of better taste. This is feedback from an operational outcomes measure to an operational objective. You hope this translates into improved revenue. Finally, after a few months (business measures often lag!) you see your new revenue numbers and determine whether the taster’s expert opinion is reflected in your business performance, completely closing the feedback loop relevant to your process changes. Note that no matter how expert your taster is, she might not have gotten it right. It could be you need to try again, and without business measures you can’t know for sure. Thus you need all three levels of measurement to properly close a process feedback loop.

Simple Steps to Measuring (Closing the loop!)

With the three-tier measurement loop understood, we can outline some steps to measuring. These steps leverage GQM[ii] – Goal/ Question/ Metric, an important tool for getting measurements right.

- Take stock. What are you measuring today? If the answer is “nothing” then skip to step 4.

- Of those things you are measuring, which of them are you using to answer important questions about your capability, or your progress toward a process decision/directive, or operational objective, or business goal? Keep those.

- Of those things you are measuring, which are you not using in a way that can help improve measured results? If they’re completely automatic and won’t go stale, you can do nothing with them for now. However, if you invest effort to measure them, now is the right time to stop performing those measurements.

- Now that you have surveyed your existing measurement landscape, what more are you asking about (GQM’s “Q” for Questions) whose knowledge would improve your business results against your business goals (GQM’s “G” for Goal)? This will require knowledge of how you translated your desired business goals into operational objectives, and in turn how those have been translated into process directives. What do you need to measure to know that your process decisions are being carried out? What do you need to measure to know that your outcomes against your operational objectives are improving? What do you need to measure to know that your desired business results are being achieved?

- From the list in step 4, pick no more than one item in each tier – because we should start small and simple. (GQM’s “M” for Metric.) Pick at least one item in the bottom (controls) tier.

- Implement the (up to) three measures you just picked. The implementation can be manual if that’s easier until it is understood that you have it right – that it’s answering your questions. Once you know you have it right, you must automate each measure if you can.

- If you cannot automate a measure that you need, then understand the business case for the measure in monetary terms. It won’t be long before someone is asking after the high cost of the measurement, and you will need to justify the expense by demonstrating the value that accrues from the measure.

- Do it now. It is most important to realize that most companies are measuring very little that they need to measure. Without closing the loop, you have no objective way to improve. Go measure something useful!

- Add or remove about one measure at a time with some reasonable frequency. Keep it simple, keep it small, but no smaller than needed.

Practical Measuring Guidelines

- Measure what you need to measure. This sounds simple but it is not. Many things are easy to measure; they are your tool’s default or whatever. However they often aren’t worth much. As previously mentioned, Douglas Hubbard notes the high cost of getting this backwards. Corollary: look often for measures you need, and start measuring them.

- If what you need measured is expensive to measure, then develop a (lightweight) business case for it; don’t just abandon it due to cost. If you think you need it, your gut is telling you that it’s worth the expense, so do the analysis to know, and fight for it if it’s worth the investment. Suggestion: you may need to account for substantial uncertainty in the business case. That is a separate topic …

- Do not measure what you don’t need. Most measures that you don’t need waste time and effort. They also get stale and present false or misleading information. Corollary: it’s entirely reasonable to stop measuring something no longer needed. Corollary: look for stale measures often, and remove them, especially if there is any chance they can become stale and/or present false/misleading info.

- Measure a little, not a lot. One or two good measurements are more valuable than 10 poor measurements.

- Anything can be measured. Douglas Hubbard asserts this[iii], and I have found it to be true. Corollary: if you need it, then don’t give up.

- All measures should be visible and available. Make a good dashboard. Your measures are trying to tell everyone something, but if they’re hard to find, no one will hear, which is both a waste and a failure to close necessary feedback loops. Thus, a reasonable dashboard is always worth the expense of creating it.

- No measurement need be automated until you know it is a measure you need. But …

- All measurements you need shall be automated as soon as possible. Failure to do so leads to expense, drudgery and fudgery, especially fudgery, otherwise known as making stuff up.

- “If you measure nothing else, measure the Cost of Delay.” (COD) This is Don Reinertsen’s principle[iv], oft-repeated by Dean Leffingwell and for good reason. This may be Reinertsen’s most important principle, as it leads to less waste, better flow, and system-optimal behaviors. It is also the basis for the prioritization tool WSJF[v].

- To determine what you need to measure, use Vic Basili’s GQM – Goal, Question, Metric. The Wikipedia page on GQM is as good a place to start as any and is referenced previously. What are your goals? Use them to determine your questions. Determine the metrics needed to answer your questions and then implement them. Wikipedia specifies 6 steps and you should follow all 6. I often think of the word metric as the identifier for the elements needed to answer questions, and then measurement is the mechanism and implementation for actual data collection of that which the metric identified. It can pay to be precise in this way about the nomenclature.

- Identify improvement goals

- Generate questions

- Identify potential measures

- Introduce mechanisms for data collection

- Collect, validate, analyze the data to provide feedback

- Take action

- Think of measures as being in three tiers – the business results, operational objectives (both are outcome measures), and process control measures (i.e. not outcomes) of which I wrote in a section above. By the way, an extensive set of Agile-related control measures can be found behind the Agility Health Radar(AHR) intellectual capital, see here[vi].

- Post and well socialize these guidelines. Everyone needs to know and follow them. Your Center of Excellence might be a good “place”.