I am motivated to write this entry on geographically distributed Agile teams because most clients now, at least those of significant size, seem to have issues stemming from this situation. Indeed, a timely tweet from Scott Ambler on 27-April-2018, referencing his 2016 Agile At Scale survey, says it all: “Less than one-third of #agileteams are co-located! http://dld.bz/fxnJr Isn’t it amazing what surveys discover?”

I have seen three major reasons/scenarios for geographically distributed teams, and I am sure there are more reasons I’ve not seen yet:

- Our company is ginormous (technical term!). Most of us jumped onto the big “offshoring”[1] bandwagon because our CFO was so excited to see the reduced development costs that we projected would result. However, we didn’t effectively consider the impact on value associated with offshoring, including the reduction in collaboration that would result from offshoring. Collaboration between team members “on the other side of the world” is very difficult.

- Our company is ginormous, and we got this way by buying other companies. Sometimes their offices were located many timezones away. As we merged, people were placed in fragmented fashion onto teams based on functional expertise. Now we have teams where members are in multiple timezones, some having been on the acquired company, and others on the acquiring company, and the cultures are still far apart.

- The technology was developed in, say, China, but it is applicable only or mostly to, say, a US and/or European market. Our dev teams are in China because that is where the technology expertise resides. However, our product owner needs to be in the US and Europe, where the market for the product is understood. Therefore we have split our teams up in that fashion. It is a constant struggle to keep the bandwidth of collaboration sufficient between the dev teams and the product owners.

A common coaching pattern that arises from this situation occurs when an Agile coach consulting to such a company inevitably perceives collaboration difficulties. S/he asserts that one of the root causes of the collaboration difficulties is that the teams are not collocated, and/or that they spend insufficient time interacting face-to-face. After all, the agilemanifesto.org principles[2]are clear:

- “Business people and developers must work together daily throughout the project”,

- “The most efficient and effective method of conveying information to and within a development team is face-to-face conversation”.

My call to the coaching community is simple: this is no longer a useful answer. That may be the beautiful horse we rode in on, but the horse has a broken leg and we need to put it out of its misery. Too few clients can, or will, take the advice. Scott Ambler’s numbers bear this out. To help make our client successful, we need to recommend something else. We can start by asking, “What if I said, ‘You have to collocate your teams?'” but they are usually going to tell you that’s not an option, and sadly, they mean it. If you persist, then their response may well be, “We don’t need you – you are no help to us.”

My call to the coaching community is simple: this is no longer a useful answer.

What shall we tell them instead? How do we make our client successful? I don’t yet know. I haven’t gone down this road enough times yet. But I’ve developed some options, and I’m interested in knowing if you’ve tried any of these options, how successful they have been, and what other options we need to begin also recommending to our clients. Some definitions help to get us started, and Scott Ambler in this article ([3]) does a good job with the definitions – indeed, the entire article is excellent.

Coaching Options for non-collocated teams

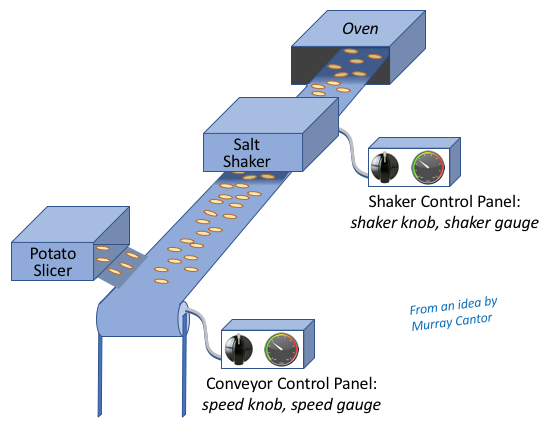

- Invest in really good collaboration technology. I mean the kind that just works, and initializes in seconds. It’s available, I have seen it, and it really helps. You walk into a conference room, you push a button or dial a number, and there on the screen in the front of the room is another conference room, half way around the world, and your mates are there, and the video is clear, and the audio is clear, and screen sharing is easy. It just works, and it takes 15 seconds not 15 minutes to initialize. I don’t know how much it costs to get that, but its justification is probably there in the time being wasted, along with the frustration and distraction. It’s certainly there if you miss a market window or fail a quality gate because you can’t get the needed level of collaboration. An Agile principle covers this: “Build projects around motivated individuals. Give them the environment and support they need, and trust them to get the job done.”

- Look for an early opportunity for people frequently collaborating to meet in person, face-to-face, at least once. And again when possible. It makes a huge difference.

- Look for patterns to improve collocation and cross-functionality. Agile teams that are not cross-functional are problematic. The way I often tell it, “If Fred isn’t here today, you can wait until tomorrow for Fred, who will do the task by himself in an hour, or you can assign two people to do the task Fred normally does. Even though they’ll take twice the time and four times the manpower, they’ll learn how Fred does it, might even figure out a better way, and the rest of the team will be awaiting the result for only 2 hours instead of 8 (or 24).” Once again, Agile principles cover the situation: “The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams.” And (derived from Lean) “Simplicity–the art of maximizing the amount of work not done–is essential.” A Scaled Agile principle[4]also applies, “Apply systems thinking.”, i.e. optimize globally not locally.

How do these principles manifest here? Well, suppose we have two distributed teams, and both are half in a Philadelphia office and half in a Mumbai office. Take the parts of the two teams in Philadelphia and make them a team. Take the parts of the two teams in Mumbai and make them a team. For awhile, it may be that neither team performs well. They’re missing skills! But they will acquire those skills. A pattern like this for reorganizing teams to make them more collocated and more cross functional can usually be found amongst the teams in a distributed organization.

- Be extremely loath to place individuals in situations where they are working by themselves, e.g. with no office or in a different city from everyone else. They never get to collaborate with high bandwidth, and honestly that’s just depressing. Actually, I’ve seen this several times recently and it didn’t seem depressing at all to the people involved, and I wondered why. I eventually realized that the people in these situations do not realize what they are missing. Contacting someone several times and finally getting them to cooperate, followed by calling the person several more times and finally getting them to do it right, seems normal to these people. The people involved often are those who the company believes are true experts and SMEs, so it doesn’t seem unusual to anyone that conveying what’s really needed is difficult and will take time. I think that’s hogwash. When they collaborate in person it does not take nearly as long, and the result is usually higher quality.

- Moreover, such people are fragmenting their capabilities by having too many things on their plate, which Agile would call a high WIP limit, so their efficiency is reduced that way too. That group of people known as architects seem to have this problem very often. I’ve spoken to many architects who wish they could do their day job, but instead they spend the whole day telling the next team what the architectural guidelines, patterns and constraints are that apply to that team. There is too much information in their heads, and too much of it is known only to them! (I’ve heard this referred to as low truck number – if they get run over by a truck…) Experts/SMEs must write down the basics, and refer practitioners and teams to what’s written first, socializing the location of that information. That way when there is a conversation, it doesn’t start with the basics, it starts with the exception of interest – this is higher bandwidth.

- When you have a distributed team, you need the skills of a Scrum Master in each location. The Scrum Masters should meet regularly. One should be a chief of sorts for the team.

- When you have a distributed team, you need the skills of a Product Owner in each location. The Product Owners should meet regularly. One should be a chief, who absolutely must have absolute final say (did I sufficiently emphasize that?). However, there is no issue with one of the Product Owners making a decision that is later undone by the chief Product Owner. She was doing her best, and most of the time she’ll make the right decision, avoiding blocking the team. When she has a miss, not much work must be undone because she and the chief PO meet regularly. (SAFe® principle #9: “Decentralize decision making.”)

There are a number of large-organization antipatterns we can recognize also, and coach to improve:

- Antipattern: IT is a Cost Center. This is never true. To prove it, next time you hear “My IT Department is treated as a Cost Center”, offer that they should all turn the lights out and go home. The lowest cost I can offer to my company is to cost them nothing, right? The refrain will be immediate: you can’t do that! Well why not? You wanted me to lower costs and I have done so. But the IT Department provides… whatever they say next, it’s value. It’s worth money. Determine the approximate monetary value if you must, to make your point. IT is a Value Center, and everyone needs to treat it that way.

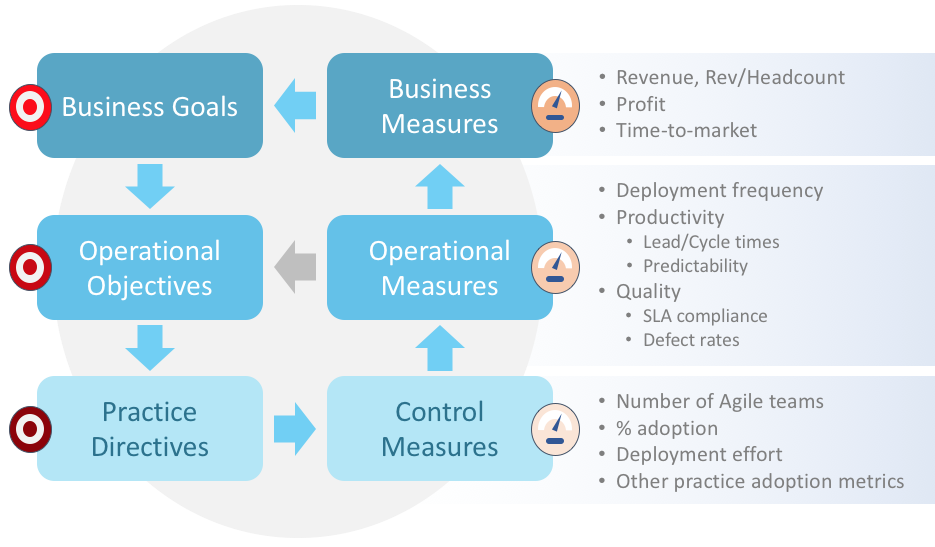

- Antipattern: we must measure Productivity and Utilization. Gaaah. If you measure utilization, you stifle your teams. Lots of studies out there demonstrate this. I spent much time in my youth going after productivity measures. They’re worthless. Measure predictability and value accrued. Measure cost of delay. (Don Reinertsen: “If you measure nothing else, measure the cost of delay.”) But don’t measure productivity or utilization of knowledge workers.[5]

- Antipattern: SMEs and other True Experts can work alone. Nope, not really. It’s not very efficient and it’s ineffective. See my coaching discussion bullet above.

- Antipattern: SMEs and other True Experts don’t need to document their knowledge. Yes they do! Use the SAFe® concept of capacity allocation[6]to ensure that documentation of things the Expert seems to say all the time is getting performed regularly. Socialize the location of that information. Use it to raise the bandwidth of the next conversation.

- Antipattern: We support our meetings with frustrating collaboration technology. Oh my golly this happens so often you would think they actually word their goal exactly that way. You walk into the conference room and the technology isn’t ready for another 15 minutes. Incredibly wasteful, very frustrating and distracting too. This comedy video is just depressing, ain’t it? ( [7])

- Antipattern: We’ll ignore the latest acquisition’s effect on overall product architecture; they’ll figure it out. This is a simple application of Conway’s Law[8], which, roughly stated, is “Organization drives architecture.” Mel Conway said “If you have four teams writing a compiler, you’ll get a four pass compiler.” You can’t ignore the acquisition in this way. Figure out what the end architecture is that you want, and mold the whole development and delivery organization around that architecture. Just do it.

- Antipattern: We ignore cultural differences during an acquisition. This is what killed Daimler-Chrysler.[9]

Finally, I have an update to this post, my colleague Bob posted this blog entry in May 2020 and I find it quite germane. I hope this helps as you work to improve the effectiveness of your distributed Agile teams.

[1]Offshore is a term I dislike, but it is in common usage so I am using it in these pseudo-quotes. In India, it is the US that is offshore. Let’s just say where the people are, e.g. U.S., India, China, Ireland … wherever they are. While we’re at it, let’s call those resources people, or human beings, or team members, since that is what and who they are.

[2]agilemanifesto.org and its page www.agilemanifesto.org/principles.html

[3]http://www.disciplinedagiledelivery.com/agility-at-scale/geographically-distributed-agile-teams/

[4]https://www.scaledagileframework.com/safe-lean-agile-principles/

[5]References include SAFe® Principle #8: “Unlock the intrinsic motivation of knowledge workers”, and Dan Pink’s books, or even just his video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u6XAPnuFjJc.

[6]Search for “Optimizing Value and Solution Integrity with Capacity Allocation” here: https://www.scaledagileframework.com/program-and-solution-backlogs/

[7]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kNz82r5nyUw

[8]http://www.melconway.com/Home/Conways_Law.html

[9]https://www.forbes.com/sites/georgebradt/2015/06/29/the-root-cause-of-every-mergers-success-or-failure-culture/#7812cdcd305b