Summary

The Scaled Agile Framework® (SAFe)[i] contains a method for initializing and normalizing an Agile team’s effort and/or complexity estimates, the use of which can result in poor behavior by Agile teams. In defending this claim of danger, this paper first discusses Planning Poker and Story Pointing in Scrum as background information, and highlights the importance of relative and unanchored estimating. A brief discussion of SAFe®’s normalized story point estimation method follows. Poor behaviors observed on teams at a recent client of the author’s is then discussed. SAFe®’s normalized story point estimation initialization technique is hypothesized as part of the cause. Finally, a brief discussion of a proposed solution is offered. A followup paper is proposed if necessary that would discuss solutions that have been tried, and their level of success.

Planning Poker and Story Points – background

In Agile/Scrum[ii], story pointing is a method for estimating the amount of work to be done by a development team over a period of time in a predictable manner. It is usually done by a team via an estimating procedure called Planning Poker[iii], which yields a relative estimate for the work to complete a requirement based on a small reference requirement whose baseline point value is arbitrarily assigned, usually 1, 2 or 3. It is called story pointing because story point values have no units (this means they do not refer to hours or any other duration or cost), and because the requirements in Agile/Scrum take the form of use case-like statements called user stories[iv] which contain a user role, a statement of functional need, and a statement of value.

Planning Poker is a variant of an estimation method developed in the 1950s-60s at the Rand Corporation called Delphi. The Delphi Method[v] is a systematic, structured communication method that includes participant anonymity and simultaneity (avoiding the influence of other participants), a consensus basis, and regular feedback (each of which contributes to gaining agreement and commitment). Barry Boehm and John Farquhar originated the Wideband[vi] variant of the Delphi method in the 1970s, calling it wideband because the new method involved greater collaboration among those participating. Finally, Planning Poker is a “gamified” form of Wideband Delphi.

Estimates in Planning Poker take the form of a number in a (modified) Fibonacci sequence[vii]. That is, suppose our reference story is assigned 2 story points; then a relative estimate of the work for some other user story might be 2 (roughly the same effort and/or complexity[viii]), or 3 (a bit more), or 5 (more), or 8 (a lot more[ix]), etc. Many cite that the reason for using relative estimating and Fibonacci is to reflect the inherent uncertainty in estimating larger items[x] and to avoid equating the relative estimates with specific time units like hours. The industry also has found empirically that relative estimates yield better predictability properties for a team[xi].

The Fibonacci sequence has the interesting property that the ratio of Fn+1/Fn converges (i.e. limit as n approaches infinity) to an irrational number called the Golden Ratio[xii] phi = (1+5^0.5)/2 = 1.6180339887…

Phi appears surprisingly often in nature, such as the arrangement of leaves and branches in plants, the proportions of chemical compounds and the geometry of crystals. Its use in Planning Poker (via the Fibonacci sequence) is – perhaps due to its frequent appearance in nature -because the human mind perceives ratios larger than phi as significant in some sense, and ratios smaller than phi as insignificant[xiii]. A second reason is that it forces participants to avoid simple ratios like “twice” or “four time as big”, or “half as big”[xiv]. Using hours or days in lieu of Fibonacci-based points leaves a team free to use such simple ratios and to quibble over relatively insignificant differences unnecessarily and wastefully.

SAFe®’s Story Point Initialization

Tucked into the intellectual capital on SAFe® team-level iteration planning[xv] is the concept of Normalized Story Point Estimating. First it is acknowledged that in Scrum, each team’s velocity[xvi] is associated only with that team. However, it is asserted, in SAFe®, story point estimation shall be normalized. The reason given is that estimates for requirements such as features whose development comes from multiple teams must be based on the same story point definition. This, in turn, is said to provide a way to perform ART[xvii] and Solution-level economic decision-making on a common basis.

The following algorithm for normalizing story point estimating across multiple teams is offered by SAFe® on its team-level iteration planning page:

1. Normalize story points:

Find a story that will consume about ½ day in development and ½ day for test and validation; assign this story 1 story point; estimate your stories relative to this baseline story

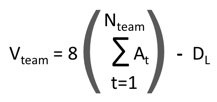

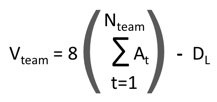

2. Establish the team velocity Vteam prior to the existence of historical data:

Let the effective team size be Nteam, i.e. the total number of developers and testers on the team

Let DL be the total number of effective team-member vacation, holiday, sick and other leave days anticipated for the iteration or sprint (for all the team members)

Then:

where At is the fraction allocation – At is in (0,1] – for each team member t, e.g. each FTE[xviii] on the team who is allocated full-time to that team has an At of 1.0.

In 1. above, it is readily seen that 1 story point is equated to 1 day’s effort. The justification for the constant 8 in 2. above is similar, at least in the SAFe® SPC training class attended by the author: in a two week sprint, there are 10 days, then subtract 2 days for meetings and other miscellaneous inefficiencies. In other words, in order to normalize story pointing for collaboration during cross-team story point estimating, such as in ARTs, SAFe® asks that a time-based method for estimation initialization be used.

Story Points should not be about hours or days

The first issue with this advice is that story points, while they are about effort and complexity, are not about hours or days. While it is clear that a story that has more effort and complexity takes more time, how much more varies from team to team and with the situation. Let’s hear it from one of the acknowledged experts, Mike Cohn[xix] (underlining is my emphasis):

I’ve been quite adamant lately that story points are about time, specifically effort. But that does not mean you should say something like, “One story point = eight hours.”

Doing this obviates the main reason to use story points in the first place. Story points are helpful because they allow team members who perform at different speeds to communicate and estimate collaboratively.

Two developers can start by estimating a given user story as one point even if their individual estimates of the actual time on task differ. Starting with that estimate, they can then agree to estimate something as two points if each agree it will take twice as long as the first story.

When story points [are] equated to hours, team members can no longer do this. If someone instructs team members that one point equals eight (or any number of) hours, the benefits of estimating in an abstract but relatively meaningful unit like story points are lost.

When told to estimate this way, the team member will mentally estimate first in number of hours and then convert that estimate to points. Something the developer estimates to be 16 hours will be converted to 2 points.

Contrast this with a team member’s thought process when estimating in story points as they are truly intended. In this case, team members will consider how long each new story will take in comparison to other stories. For example, you and I might agree that a new story will take twice as long as a one-point story, and so we agree it’s a two.

Knowledge and use of the SAFe® normalization approach is leading to poor behaviors

The second issue with SAFe®’s advice stems from my own consulting team’s experience with clients using the SAFe® story point normalization and initialization process. In our experience it demonstrably leads to

- being an excuse to allow anchored behavior, i.e. non-anonymous and non-simultaneous effort and/or complexity estimating by teams

- non-relative estimating, i.e. use of hours as a means to derive story points, which means of course that one might as well just use hours (at least it is more honest)

- management imposition of target velocities for teams as a misguided productivity motivator[xx].

With regard to the last bullet, let’s remind ourselves that in order to double a team’s velocity so that they can meet a target velocity imposed on them, all the team needs to do is halve the size of the reference requirement or user story, or double the number of story points assigned to that reference story.

Solution

“Help Teams excel, don’t punish them.”[xxi]

SAFe® claims that story point normalization is needed “so that estimates for Features or Epics that require the support of multiple teams are based on the same story point definition, allowing a shared basis for economic decision making.[xxii] The author does not buy this argument. Each team has a run-rate (cost per unit time), and each team commits to developing a certain set of requirements, and therefore value, in each 2 week iteration and/or in each 10 week program increment23. That value is sufficient to determine the economics of the situation where tradeoffs are necessary; such tradeoffs take place no lower than at the team level anyway. Moreover, the team who has a history performing using Scrum who is subsequently assigned to an Agile Release Train arrives at the Train’s first PI Planning[xxiii] meeting with an unnormalized velocity already in place. One should be reluctant to disturb the team’s existing velocity.

Suppose a team is assigned to an ART, and is also just starting to use Scrum. How should such a team in an ART initialize their velocity? Despite several expert Scrum sites that warn against anchoring using time, only to propose a time-based initialization method just as does SAFe®, (e.g. [xxiv] )!, VersionOne suggests what may be a better procedure: “Initially, teams new to Agile software development [with Scrum] should just dive in and select an initial velocity using available guidelines and information.”[xxv] That is, you know your team, just give it your best shot! Remember, this exercise starts with a reference user story, that story to which an arbitrary story points value was assigned – be that value 1, 2, or 3 (since different Agile sites suggest each of these three arbitrary values early in the Fibonacci sequence). Will your initial velocity be right? Quite unlikely! The goal is not the impossible one of being predictable in your very first sprint. The goal is the continuous improvement of the team’s predictability over time. Predictability is valuable[xxvi] because it generates trust. This is a good goal.

Epilogue … not everything transcribed well from the original Word document. Please let me know if you see any errors, thank you.

[i] Dean Leffingwell’s framework for scaling Agile development, – see http://www.scaledagile.com (corporate/administrative) and http://www.scaledagileframework.com (technical, and by the way, highly “clickable”)

[ii] What is Scrum? : https://www.scrum.org/resources/what-is-scrum?gclid=Cj0KCQiAyZLSBRDpARIsAH66VQItwbMIu3mxrGvzBy2P-ZWhn9AhkWLTbN7yY7q3fYr_Z8-9vnBRrogaAnl0EALw_wcB

[iii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Planning_poker

[iv] https://www.mountaingoatsoftware.com/agile/user-stories

[v] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delphi_method

[vi] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wideband_delphi

[vii] The Fibonacci sequence, defined by Fn+2=Fn+1+Fn where F1=1 & F2=1 (or optionally F0=0 & F1=1), starts with (optionally) 0, then 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, etc. Regarding “modified”: one always modifies the sequence for use in estimating by including only a single 1. Additionally, perhaps because it’s easier to think about these numbers, larger numbers can be rounded, e.g. 20, 40, 100 instead of 21, 34, 55, 89, and sometimes more esoteric values are included such as 0 (meaning trivial), ½, infinity, “?” and the flippant “I’ll go make some coffee”. One such scheme is codified in a commercial card deck product: https://store.mountaingoatsoftware.com .

[viii] This intentionally avoids the current discussion in the literature about whether story pointing should be based on effort (per Cohn and others, e.g. https://www.mountaingoatsoftware.com/blog/dont-equate-story-points-to-hours) or complexity (per Giddings and others, e.g. https://www.clearvision-cm.com/blog/why-story-points-are-a-measure-of-complexity-not-effort/)

[ix] Why the phrase “a lot more” instead of “four times more”? After all, 8/2 is 4. The answer is that some experts/authors don’t believe it is correct to make that assumption, in particular because of the presence of uncertainty in the estimate. As with the complexity vs. effort argument referenced earlier, discussion of that topic is being intentionally avoided.

[x] It has been difficult to find where this was originally stated. Wikipedia’s Planning_poker page says “citation needed”. Several other references were consulted, and they either make this statement without citation, or they cite Wikipedia. A reasonable guess is that it’s in one of Mike Cohn’s books. Stack Overflow, at https://stackoverflow.com/questions/9362286/why-is-the-fibonacci-series-used-in-agile-planning-poker, contains the amusing statement that this description on Wikipedia holds “the mysterious sentence” and then echoes the phrase, “reflect the inherent uncertainty in estimating larger items”. Regardless, the author believes the statement to be reasonably accurate.

[xi] http://blogs.collab.net/agile/perfectly-predictable-why-story-points-are-better-than-detailed-estimates and http://gettingpredictable.com/the-attitude-of-estimation/

[xii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_ratio

[xiii] I swear I have read this before! and it was in a decent reference; I am searching desperately for the citation, yes indeed … but I have not yet found it

[xiv] https://www.scrum.org/forum/scrum-forum/7897/why-do-we-use-fibonacci-series-estimation

[xv] http://www.scaledagileframework.com/iteration-planning/

[xvi] Velocity: as used here, velocity is a key to improving the predictability of an Agile development team. Velocity is an assessment of how many story points a single team can commit to achieving, or performing, in a single iteration or sprint. When a team has a history of prior sprints’ story points achievement, velocity is some reasonable function of that history – the function is determined by the team but an average is a good start. When the team has no such history, this is when SAFe®’s normalization/initialization process might be applied. Scrum.org has a good page (https://www.scruminc.com/velocity/) on velocity:

Another good page on velocity is: https://www.scrumalliance.org/community/articles/2014/february/velocity .

[xvii] ART: a SAFe® Agile Release Train, SAFe®’s organizational structure for multiple, persistent Agile development teams; see http://www.scaledagileframework.com/agile-release-train

[xviii] FTE: full-time employee

[xix] https://www.mountaingoatsoftware.com/blog/dont-equate-story-points-to-hours

[xx] https://vimeo.com/49263000 is a superb video by Dan Pink which speaks to how real motivation of knowledge workers arises.

[xxi] https://www.scrumalliance.org/community/articles/2014/february/velocity

[xxii] http://www.scaledagileframework.com/iteration-planning/

[xxiii] http://www.scaledagileframework.com/pi-planning/

[xxiv] https://stackoverflow.com/questions/1232281/how-to-measure-estimate-and-story-points-in-scrum “… start out by assuming a story point is a single ‘ideal day’ …”

[xxv] https://www.versionone.com/agile-101/agile-management-practices/agile-scrum-velocity/

[xxvi] https://dzone.com/articles/predictability-really-what-we , https://uxmag.com/articles/being-predictable ; also information on predictability metrics: https://www.leadingagile.com/2013/07/agile-health-metrics-for-predictability/ , http://www.scaledagileframework.com/metrics/#P2 ,